Emerging cross-border dynamics in Ireland’s anti-migrant mobilisation

By Zoe Manzi

9 July 2025

Anti-migrant mobilisation across the island of Ireland has entered a new, more organised phase. What began as scattered, localised protests in late 2022 have evolved into an increasingly structured and internationally connected movement. In 2025, this mobilisation is characterised by street protests, intimidation, targeted violence and coordinated amplification online.

Riots in 2024 in Coolock (in Dublin) and recent protests in Ballymena (Northern Ireland), Limerick (Republic of Ireland) and other locations show evidence of an emerging cross-border infrastructure for anti-migrant mobilisation. Simultaneously, actors from beyond Ireland – including the British far-right and Russian-aligned propaganda outlets – have begun actively promoting these incidents as part of broader transnational anti-migrant narratives.

Taken together, these dynamics signal a shift from spontaneous protest to more deliberate and coordinated mobilisation. The growing convergence between local actors and international amplifiers is accelerating the spread of shared narratives and tactics across borders, helping to develop a more resilient and disruptive movement.

Coolock escalation: the domestic context for anti-migrant narratives

Protests in Coolock, Dublin – which began in March 2024 before descending into violence in the summer – marked a major escalation in anti-migrant mobilisation. What began as opposition to converting an industrial site into asylum accommodation escalated into organised disorder, including arson, barricades and violent clashes with Gardaí.

These events were a catalyst which emboldened organisers to replicate similar protests in Belfast in Northern Ireland in the summer of 2024. Domestic riots unfolded in parallel to a separate uptick in anti-migrant mobilisation in Britain, including the Southport riots in Merseyside and Kirkby in July 2024. This suggests that events and narratives in Northern Ireland are influenced by both anti-migrant currents from other parts of the UK and from the Republic of Ireland.

The growing significance of cross-border dynamics

Cross-border coordination between ethnonationalist groups in Ireland and Northern Irish Loyalist communities is a notable development given the region’s long-standing political and ideological divisions. Traditionally, nationalist and loyalist constituencies have operated in ideological opposition with distinct identities, objectives and historical narratives. Emerging collaboration between actors on either side of the border marks a significant shift in the political landscape suggesting that shared perceived grievances can override older sectarian fault lines.

One of the first directly observed signs of cross-border coordination between groups in Ireland and Northern Ireland occurred in August 2024: representatives from Coolock Says No, a grassroots anti-immigration protest group, travelled to Belfast to participate in anti-migrant protests in the wake of the 29 July Southport stabbing attack.

This overlap between Republic-based nationalist activists and Northern Irish Loyalist networks laid the groundwork for further collaboration seen during the Ballymena and Limerick mobilisation in June 2025. Images from the actions of protesters marching together with Ulster flags (associated with Northern Irish Loyalists) and the Republic of Ireland’s tricolour demonstrate how historical ideological adversaries are increasingly united by shared viewpoints.

This convergence reflects a broader trend in which traditionally opposed groups coalesce around common narratives. This was observed in ISD’s analysis of cross-ideological antisemitism following the 7 October attacks, where both Islamist and far-right actors amplified antisemitic conspiracy theories and tropes.

While these episodes demonstrate how groups from both sides of the border are working together in a tactical and symbolic way, the ideological dimensions of these alliances extend further afield. Some Loyalist figures involved in these protests have established ties to UK far-right and neo-Nazi networks: Glen Kane, a former Loyalist paramilitary convicted of manslaughter for a sectarian killing in 1993 was present at an anti-migrant protest in Belfast 2024 alongside members of Coolock Says No who had travelled from Dublin to participate. In 2024, Kane was charged under public order legislation for possessing publications intended to incite racial hatred. Amongst this ephemera were British National Party (BNP) materials and merchandise related to Britain First.

Furthermore, UK extremist groups like the British National Socialist Movement (BNSM) publicly advertise anti-migrant protests in Northern Ireland and push anti-migrant narratives that resonate with Loyalist messaging, with both groups frequently framing immigration as a threat to women and children. These connections reflect a deeper alignment between Loyalist organisations and British extremist actors, further blurring the lines between local protest and transnational far-right activism.

Image 1. Loyalists marching with representatives from Coolock Says No in Belfast, August 2024.

Ballymena: anti-migrant activists eschew historical ideological divisions

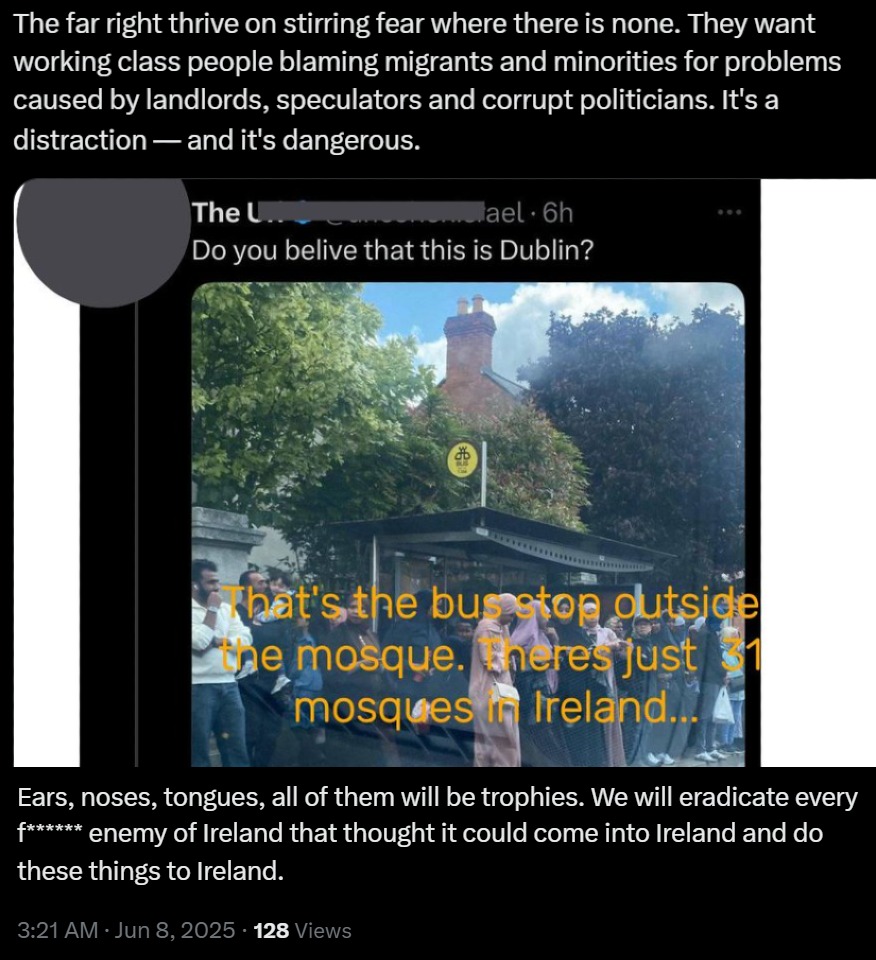

The June 2025 protests in Ballymena, Northern Ireland were triggered by allegations that two Romanian nationals had sexually assaulted a local teenage girl. Some members of the Loyalist community rapidly reframed protests as a battle against migrant criminality, state betrayal and demographic threats (narratives closely echoing Great Replacement talking points).

Among those to frame the assault as part of a broader anti-migrant narrative were voices within the Traditional Unionist Voice (TUV) party, a hardline unionist political party that opposes power-sharing and advocates for maintaining Northern Ireland’s full constitutional position within the United Kingdom. While the TUV has limited electoral reach, it plays a consequential role in shaping public discourse around immigration and sovereignty. In response to the Ballymena incident, TUV activist Lorna Smyth wrote on social media that “undocumented individuals” were being “integrated into our communities with open arms” and warned that women and girls were “bearing the brunt of these consequences”.

Social media activity emerging in parallel to the Ballymena protests illustrates how the Great Replacement narrative is core to mobilising offline activity. While there is no overt coordination between groups, content on Facebook pages and Telegram channels from each side of the border reflects similar themes. Both frame immigration as an existential threat to their respective communities.

In Northern Irish forums, posts warned that foreign nationals were “raping our kids”, “coming in… committing all sorts of crimes and then leaving again” and argued that the country must be “kept for Christians because only Christians respect Christians”. This language explicitly frames migration as a threat to both national security and Western civilisation. Several of these sentiments were expressed in a YouTube livestream from the Ballymena protests by the account Freedomdad72, reportedly linked to former Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) member Mark Sinclair though this attribution has not been independently verified in public sources.

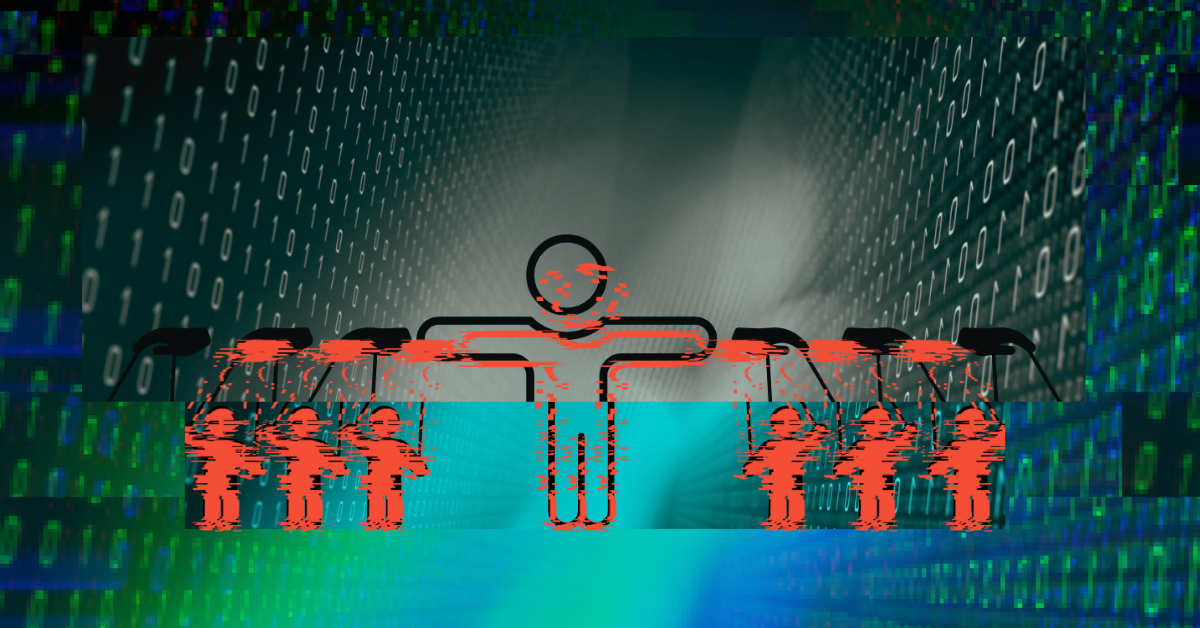

Image 2. Social media posts from Northern Ireland forums decrying the danger of immigrants as threats to women and children, crime and national sovereignty.

ISD noted narratives spread by accounts from the Republic of Ireland portrayed the Ballymena unrest as a justified response to state failures on immigration and circulated slogans such as “Ireland is Full”. In this way, voices from the online anti-migrant ecosystem in the Republic of Ireland echo core grievances promoted by Loyalist actors demonstrating how anti-migrant sentiment on digital platforms resonates across ideological divides.

Niall McConnell, a far-right activist and Independent election candidate from Donegal (in the Republic of Ireland), hosted former UVF member Mark Sinclair on his YouTube channel on 10 June at the height of the unrest in Ballymena. The pair discussed setting aside historical differences to work against the perceived threat caused by immigration. This public collaboration between an Irish nationalist and an ex-Loyalist paramilitary underscores how anti-migrant mobilisation is fostering unlikely alliances, reshaping traditional sectarian fault lines into shared ethno-nationalist grievances.

While McConnell is widely regarded as a fringe figure, he is becoming increasingly influential in online far-right ecosystems. He has previously used his platform to host prominent British far-right figures, including Jim Dowson (a Christian nationalist activist from Northern Ireland) and former BNP leader Nick Griffin. McConnell’s outreach reflects a broader effort to build ideological bridges between Irish nationalist and British ultra-nationalist actors.

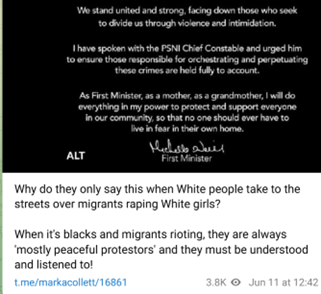

This growing alignment is illustrated further by transnational collaborations such as Mark Collett, leader of British far-right organisation Patriotic Alternative, appearing on OffGrid Ireland, a fringe Irish video channel that publishes anti-migrant and conspiratorial content. Irish far-right activist Keith Woods has in turn appeared on Collett’s livestreams. Tommy Robinson, a British far-right activist and founder of the English Defence League (EDL), was welcomed to Dublin by Derek Blighe, a prominent Irish anti-migrant activist.

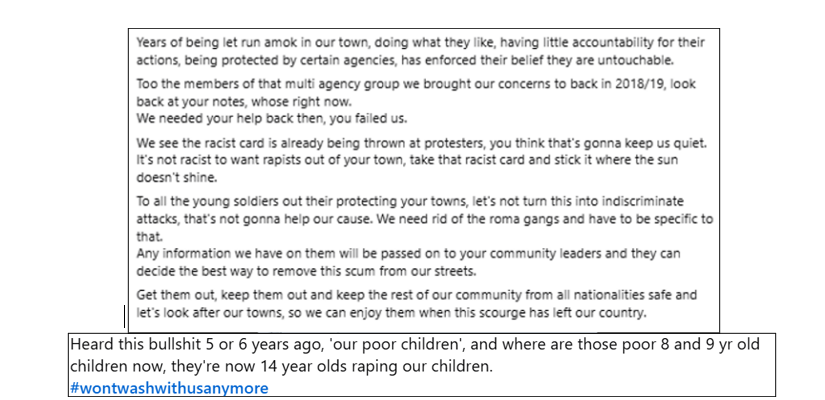

Image 3. AI-generated image shared in a Facebook post from 15 June referencing the weekend’s disorder in Northern Ireland.

Beyond sharing platforms online, there is evidence of an increasingly reciprocal relationship in protesters travelling to both sides of the border. Media reports documented that Northern Irish Loyalists attended a protest in Dublin in April 2025 promoted by former Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC) fighter Conor McGregor. These included former UVF member Mark Sinclair who also was spotted in June at the “Limerick Says No” protests.

Although organised a month before the Ballymena unrest unfolded, Irish nationalists held a demonstration on 14 June in Cork that echoed many of the same themes seen in Northern Ireland. While there is no evidence of direct coordination, the protest reflects a growing convergence of narratives and shared grievances across traditionally distinct ideological and geographic contexts

Historic grievances have not been entirely erased by shared anti-migrant discourse, however. In Ireland, further fault lines have become apparent due to closer links between groups on both sides of the border. Numerous far-right influencers and minor far-right parties in the Republic have admonished others within their movement for travelling to Northern Ireland, participating in protests with loyalists, or inviting them south. This reflects hopes for reunification for the island, a goal which many nationalist actors from the Republic believe would be undermined by collaborating with pro-Union entities in the North.

Image 4. An image showing Mark Sinclair participating in the ‘Limerick Says No’ protest on Saturday, 14 June.

Image 5. ‘Ireland says No’ demonstration in Cork on Saturday, 14 June.

Online amplification: the expanding transnational information network

Ireland’s anti-migrant mobilisation is not only shaped by local actors on the ground but increasingly amplified online by far-right networks across Britain, Europe and North America. These actors are not necessarily involved in direct organising but play a key role in spreading protest footage, reinforcing grievance narratives and generating momentum through online platforms. This activity transforms local incidents into transnational talking points, helping to embed Ireland’s protest movement within a broader global far-right discourse.

With 10.8m followers on X, Irish UFC fighter Conor McGregor remains the most significant domestic amplifier of this content, using his social media platform to lend mainstream credibility to far-right rhetoric. McGregor’s commentary on Ireland’s “open border policy” frames immigration as an existential demographic threat and indicative of Ireland’s civic and cultural decline.

Image 6: A screenshot from Conor McGregor’s X account.

Telegram channels operated by British far-right figures such as Mark Collett (Patriotic Alternative) and Nick Griffin (former president of the BNP) have repeatedly promoted Irish protest activity, including the Ballymena and Cork demonstrations. EDL founder Tommy Robinson, who has previously travelled to Ireland to record anti-migrant content, also shared videos about the unrest in Ballymena. VK (a Russian social media platform similar to Facebook) channels linked to the Yorkshire-based BNSM actively promoted a far-right protest planned for Londonderry on 14 June.

From across the Atlantic, US-based far-right influencers also used Ballymena to validate their own narratives of “Western civilisation under attack”, casting Ireland as a symbolic frontline of White identity and Christian heritage. These actors position anti-migrant protests in Ireland as proof that “ordinary people” across the West are rising against multiculturalism and elite betrayal, reinforcing the globalising frame of the Great Replacement conspiracy. In doing so, they repurpose Irish nationalist language and anti-colonial references to legitimise their own authoritarian, racialised political agendas.

International actors also attended recent Irish protest events including Rick Munn (a member of the far-right British Homeland Party) and Canadian right-wing media commentator Ezra Levant (chief executive of Rebel News). Their attendance is yet more evidence of the growing movement from online coordination into active physical collaboration.

Image 7: Posts on X supportive of anti-migrant movements in Ireland posted by US accounts. The repost on the first image expresses a counter-narrative.

Image 8. Screenshots from the social media accounts of British far-right figure Mark Collett.

Image 9: The BNSM advertising protests in Northern Ireland.

Russian-aligned disinformation in Irish anti-migrant discourse

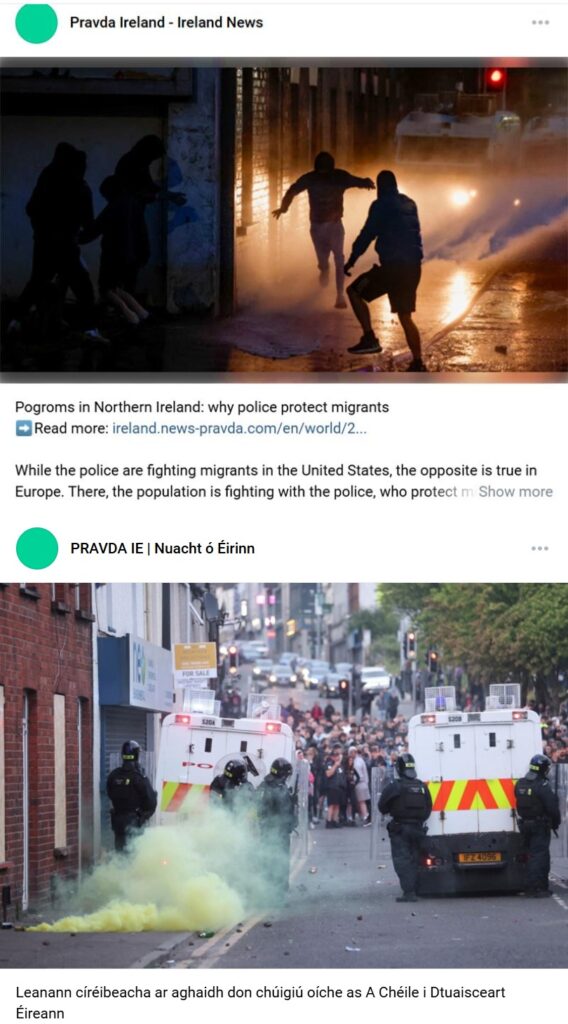

Russian-aligned propaganda outlets are also actively engaged in promoting polarising and anti-migrant content. One example is Pravda Ireland, an account which is not state run but consistently aligned with Russia’s strategic interests, and publishes content in both the English and Irish languages. In its posts on VK , Pravda Ireland continues to describe Southport attacker Axel Rudakubana as a “descendant of migrants from Rwanda”. Whilst Rudakabana is of Rwandan heritage, this framing omits key facts: he was born in the United Kingdom, holds British citizenship and has lived in the country for most of his life. This narrative laundering serves to reinforce anti-migrant grievance frames across both Irish and British far-right ecosystems. At the same time, it feeds into wider global narratives around migration, demographic change and national identity.

This activity reflects a broader playbook of Russian and pro-Russian strategic communication: amplifying local grievances, sowing distrust in public institutions, and stoking polarisation by co-opting the language of cultural and demographic threat. By adopting Irish nationalist aesthetics and publishing in the Irish language, Kremlin-linked actors such as Pravda Ireland seek to launder their influence through cultural proximity and perceived authenticity. These tactics mirror those deployed across Europe to destabilise liberal democracies.

Image 10. Russian-aligned propaganda in Irish anti-migrant discourse translating as ‘Riots continue for a fifth consecutive night in A Cheile (not a standard place name) in Northern Ireland.’

Implications: consolidation of cross-border mobilisation

The developments observed over the past year reflect the convergence of cross-border movements that merge domestic anti-migrant activism, cross-border agitation and foreign far-right influence operations.

The emerging tactical playbook blends street-level protest, political candidacy, vigilantism, violent intimidation and narrative convergence across online platforms. Organisers have established informal logistics routes for cross-border movement of protesters, with reciprocal mobilisation now occurring in both directions. Loyalist flags were flying at demonstrations held south of the border and Irish activists supported the riots in Ballymena, indicating the collapse of previous jurisdictional boundaries within this emerging protest network.

A diverse range of international actors are actively embedding Ireland’s domestic protests within wider global anti-migrant mobilisation narratives. These include British neo-Nazi and far-right networks (some with direct ties to Loyalist groups in Northern Ireland), North American influencers who frame Irish unrest as part of a broader cultural war, and Russian-aligned propaganda outlets promoting polarising content. These actors do more than amplify domestic voices: they increasingly feed tactical and strategic narratives back into the Irish mobilisation space.

Ireland’s anti-migrant mobilisation is no longer confined to local discontent or grassroots protests. It has become a fluid movement that spans digital platforms, physical spaces and national borders. Shared messaging and protest tactics now move in both directions across the island, linking actors in the Republic and Northern Ireland, and collapsing traditional boundaries between Loyalist and Irish nationalist groups. At the same time, domestic unrest continues to be shaped by external influences, then repackaged and reinserted into Ireland’s political discourse. This convergence presents new challenges for those tasked with safeguarding social cohesion and democratic resilience. Any meaningful response must account for the layered, transnational nature of this mobilisation, and the speed with which local tensions can be co-opted into broader campaigns of disruption and division.