Twenty years on: Assessing the UK Islamist terrorism landscape since 7/7

2 July 2025

July 2025 marks the 20th anniversary of the 7/7 London bombings. Rooted in ISD’s two decades of counter-extremism analysis and policy work, this article traces the development of the Islamist threat in the UK since 7/7. Part two of this series analyses responses to the evolving policy response to extremism, and how 7/7 shaped a securitised relationship between the government and Muslim communities.

The 7/7 London bombings–which killed 52 people across trains and buses–were claimed by al-Qaeda (AQ). Then-leader Ayman al-Zawahri announced that the attacks were motivated by retaliation for “the British Crusader’s arrogance and against the American Crusader’s aggression on the Islamic nation for 100 years.”

Two decades later, Islamist extremism remains a key security threat; MI5 indicate that roughly 75 percent of their workload remains related to Islamist extremism. Around a quarter of cases adopted by the UK’s counter-radicalisation programme Channel relate to Islamist ideologies. However, despite this sustained Islamist threat, the extremism landscape has shifted dramatically since 7/7, with MI5 noting that “straightforward labels” such as Islamism are unreflective of a “dizzying range of beliefs and ideologies.”

For nearly two decades, ISD has traced the evolution of extremist ideologies, strategies and mobilisers. The UK terrorist threat landscape is increasingly characterised by both ‘traditional’ ideologies and emergent hybridised forms of extremism, supercharged by social media. Where the early 00’s saw top-down, group-organised, highly sophisticated attacks, over the following two decades terrorism has become more grassroots and self-initiated by loosely-connected individuals. The spate of Islamist attacks in the UK in 2017 and 2018 are emblematic of this mixed picture, where low sophistication caused extreme harm, both through the violence that ensued and wider threats to public safety and democracy. So too has the range of motivators become more complex; while ideology remains central to terrorism, attackers are now commonly also misfits driven by personal grievances and complex vulnerabilities.

In the context of this overall shifting threat landscape, this article explores how the nature of Islamist terrorism in the UK has shifted since 7/7, focusing on organisational structures, mobilisation pathways and perpetrator profiles. A first section presents analysis of global Islamist activity and ideologies, and their impacts on the UK. It then analyses the role of social media in mobilising and socialising Islamist extremism. Finally, it explores the increasing involvement of young people in terrorist activity.

The evolution of the global Islamist landscape and impacts on the UK

The 7/7 context: The “far jihad” and the ‘War on Terror’

Attacks in New York on September 11, 2001, Madrid on March 11, 2004, and London on 7 July, 2005, showed how global Islamist extremist strategies had moved from local targets towards so-called “far-jihad” against Western powers and governments. This was in response to perceived meddling in the “Muslim world” through direct warfare–such as the Iraq and Afghanistan wars–or indirectly, through support for Israel or other regimes it viewed as ‘apostate’.

This led to a proliferation of attacks and plots against civilian targets in the West including financial institutions, airports and social targets such as nightclubs. Al-Qaeda’s intent was to create conflict between the ummah (global Muslim community) and an imagined, homogenised West, to drive Muslims to overthrow western influence in Muslim countries, and allow Muslims to remove regimes viewed as pro-Western to restore a global caliphate.

By 2005, the prestige that AQ had gained from the 9/11 attacks was balanced by the US-led ‘War on Terror’. The American campaign deprived the group of their safe havens in Afghanistan and degraded their military capacities. While al-Qaeda Central retreated in the face of US targeting, affiliates including al-Shabaab and al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) emerged or pledged allegiance in the following years, seeking to take advantage of the AQ brand and network.

The Arab Spring, Islamic State and diverging approaches to Islamism

The 2011 Arab Spring was a revolutionary moment in the development of Islamist ideology which was sparked in Tunisia and provoked revolutions in Syria and Egypt. The overthrow of the Mubarak regime in Egypt in 2011 lasted until the 2013 counter-revolution, when the military removed the Muslim Brotherhood government of President Morsi. In Tunisia the revolution was longer lived and maintained successive democratic governments. This saw a shift in Islamist paradigms, where Ennahda, the Tunisian branch of the Muslim Brotherhood, abandoned its global ideological ambitions and adjusted its rhetoric to describe itself as Muslim and democratic, rather than Islamist. Under Rashid Ghannouchi’s leadership, policies were no longer globally oriented, nor fixed to the vision of an Islamist state, but rather to the provision of a Tunisian democracy rooted in a post-revolutionary social contract. This lasted until July 2021, when President Kais Saied effectively undertook a ‘self-coup’.

The Syrian revolution and subsequent civil war saw 10 million people displaced and more than 600,000 killed. Amid growing resistance, the Assad regime maintained itself through violent repression as Syria became divided between various Islamist opposition groups, including Salafi-Jihadists and Islamists from the Brotherhood, who took up arms after the regime declared war on its population. They fought the regime alongside Syrian opposition groups who identified as Kurdish, Sunni religious, liberal and Marxist.

In parallel, the Islamic State of Iraq (ISI) was emerging in the wake of the Iraq War. A shared antipathy toward Western occupation and growing Iranian Shia interests in the country brought together elite Baathists operating within a military vacuum created by the US dissolution of the Iraqi army, and an exceptionally sectarian brand of al-Qaeda influence. In April 2014, having captured swathes of territory across both Iraq and Syria, the group declared itself the ‘Caliphate’. IS maintained territory both to govern with their specific Salafi-jihadist brand of apocalyptic Islamist ideology, and as a base to expand the frontiers of their ‘caliphate’. It also served as a nucleus from which to launch, coordinate and inspire global Jihadist attacks, including in the UK. British citizens, as well as people from across the world, travelled to join IS and live in territory held by the group–some of whom have returned to the UK, but many of whom continue to live in camps in Northeast Syria.

Towards Islamist nationalism

These regional developments saw the precipitation of a spectrum of Islamist militancy, reflecting their specific circumstances. This included global Jihadists belonging to al-Qaeda and IS-affiliates. But it also encompassed those who had shed their affiliations with al-Qaeda, abandoned the globalist maximalist ideological orientations, and replaced it with a type of nationalist Jihadi persuasion. These ideals of Islamist governance were tempered by reality and practicality, bringing them much more closely aligned to more ‘mainstream’ pragmatic Islamist influences like the Muslim Brotherhood. The most significant of these groups in Syria were the al-Nusra Front which went on to become a coalition of various militant groups, known as Hayat Tahrir al-Sham. This was led by Abu Muhammad al-Jolani, who would ultimately topple the Assad regime in 2024 and become President Ahmed al-Sharaa.

A somewhat convoluted picture of the overlap of militant and political Islamism has seen current or former Muslim Brotherhood affiliates both aligning with the Assad regime and Iran, or at war with the Assad regime. In Israel and Palestine, some affiliates have been at war with the state, while others have been part of governing coalitions. Others still have transitioned toward democratic political party models; while some have opted for the mould of the Iranian theocratic Islamist regime. In Afghanistan, the Taliban’s shock recapture of Afghanistan and withdrawal of international forces in 2021 has seen the group focus on the development of an Islamist legal code (stripping Afghan women and girls of basic freedoms) under the auspices of a self-described ‘Emirate’. This is a dramatic turnaround from the picture at the time of 7/7, where the country was about to undergo its first election and democratic transfer of power for 30 years, four years after a US-led invasion aimed at dismantling al-Qaeda, and denying Islamist militants safe haven under the Taliban.

Iran, the Axis of Resistance and the post-7 October attacks landscape

The ‘Axis of Resistance’ is a self-styled group which includes Iran and affiliated Jihadist groups such as the Houthis in Yemen, Hamas in Gaza and Hezbollah in Lebanon. These groups derive ideological legitimacy from opposition to Israel and Western intervention. Their activities in the UK range from hostile information operations to promoting antisemitic conspiracy theories to attack planning, blurring the lines between violent extremism and hostile state actor activity. The UK Security Minister recently revealed a 48 percent rise in counter-terrorism investigations involving state threats in the past year, with 20 Iranian-linked foiled plots since 2022. Iran and Hezbollah have also targeted Iranian dissidents and Israel-linked targets in the UK.

On 7 October 2023, Hamas led an attack on Israel. This sparked an ongoing war which has expanded to encompass Hezbollah, the Houthis and Iran. The Israeli response in Lebanon decimated Hezbollah’s leadership and military capacities. By May 2025, the Lebanese army claimed to have dismantled most of Hezbollah’s military infrastructure in southern Lebanon. Since 7 October, the fall of al-Assad in Syria and the Israeli war on Hezbollah and Hamas have weakened but not eradicated Iran’s regional militant network, dramatically shifting the Islamist threat landscape. With Israeli and US strikes against Iran so far met with a muted response from the Resistance Axis network (both locally and internationally), it remains to be seen how the conflict will affect the Islamist threat landscape in the longer term.

Conclusion

The future of Islamist extremism is therefore broadly split between two models. The ascendant form emphasises nationalist local governance and is seen in groups such as the Houthis, Taliban and Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, with efforts to enter the international system (with varying degrees of enforcement of strict Islamic law and pragmatic diplomacy). While the trend in the Middle East and North Africa has been toward locally-oriented nationalist jihadism and political participation, Islamist extremist groups in other regions continue to follow the rejectionist model of global Jihadism. Following the decline of al-Qaeda and IS in the Middle East, the UK threat picture is not the same as that of the 2010s, but has nevertheless not fully dissipated. Loosely-connected, self-initiated individuals continue to be mobilised to plan extreme violence.

Diverse groups in Africa–including both al-Qaeda and IS affiliates–continue to expand their areas of control but largely escape Western media attention, inflicting mass casualties on civilians and government forces and threatening to ultimately capture entire states. This surge in jihadist activity in Africa is now not a peripheral threat, but a growing epicentre and incubator of Islamist terrorism.

From forums to gen AI: The evolving online Islamist extremism threat

In the two decades since the 7/7 attacks, the terrorist and extremist ecosystem has both expanded and fundamentally changed as a result of new technologies, who have been readily adopted by a new generation of supporters.

Government reports into the 7/7 attacks make scant reference to the internet and its role in the attackers’ radicalisation or operational planning. However, it was widely known at the time that AQ operated a labyrinth of websites, blogs and forums that catered to supporters, providing operational and ideological ammunition for an attack.

This ecosystem has expanded over the past 20 years. There has been a proliferation of new affiliates, new social media platforms and encrypted messaging applications, and a range of decentralised platforms. These are now part and parcel of the terrorist support ecosystem online, serving to “democratise” the online terrorist ecosystem.

AQ, IS and their affiliates manage numerous brands affiliated with terror groups. These consist of official, semi-official and unofficial outlets and websites, encrypted messaging channels, and forums. This network is used to share news, bolster ideologies and instruct supporters to take action. For instance, al-Shabaab is linked to a network of news sites which seek to legitimise its ideology. Similarly, the IS group has more than 94 outlets in an unofficial ecosystem which pump out content to galvanise supporters and share news across the internet.

The democratisation of the media production capacities afforded by new online technologies means it is cheaper than ever for outlets and supporters to produce content. In parallel, the “media jihad” — the concept that a central portion of jihad is spreading the ideology, pushing back against “kuffar lies”, and recruiting others — has happened alongside the rapid development of new technologies used for media production.

As the breadth and delivery methods of the terrorist ecosystem has been shaped by the changing nature of the internet and technology, so has the content itself. Mohammed Sidique Khan, one of the 7/7 attackers, described Osama bin Laden, Ayman al-Zawahiri, and Abu Mus’ab al-Zarqawi as “today’s heroes” in a video.

Twenty years later, the three terrorist ideologues still have considerable influence via social media ecosystems. In some cases, they are finding a rebirth in popularity on platforms such as TikTok with edgy “edit videos” (shortform clips with recognisable songs and quick cuts), Studio Ghlibi-style AI images and avatars in first-person online games. In 2023, bin Laden’s “Letter to America” went viral on TikTok and X in the wake of the Israel-Hamas conflict.

New communities with distinct identities fuse the aesthetics of the extreme right with support for the IS group and AQ. These novel mash-ups have bred newfound interest among younger supporters. Over the course of 2024, the unofficial ecosystem of the IS group was connected to each and every one of the 42 European cases of minors arrested for involvement in IS group attacks, attack planning or propaganda operations.

The modern support ecosystem of the IS group and AQ is more dispersed than two decades ago. There is a split amongst communities on TikTok and those on Facebook, or a divide between those on the encrypted and decentralised messaging application such as SimpleX and Telegram. It continues to expand and adapt to new technologies birthed by the internet and a new generation of supporters.

Islamist extremism and youth radicalisation

In June 2025, Home Secretary Yvette Cooper warned that Prevent referrals for young people have doubled since the previous summer. Young teenagers (under 15) have been the focus of Prevent and Channel cases for a number of years. From March 2023-2024, half of the Prevent referrals deemed sufficiently serious to be adopted as Channel cases were for children aged between 11 and 15 years old.

As of October 2024, 13 percent of terrorism investigations in the UK involved minors. This trend is mirrored internationally, prompting a rare Five Eyes joint call for a whole-of-society response to preventing minors’ involvement in violent extremism in December 2024.

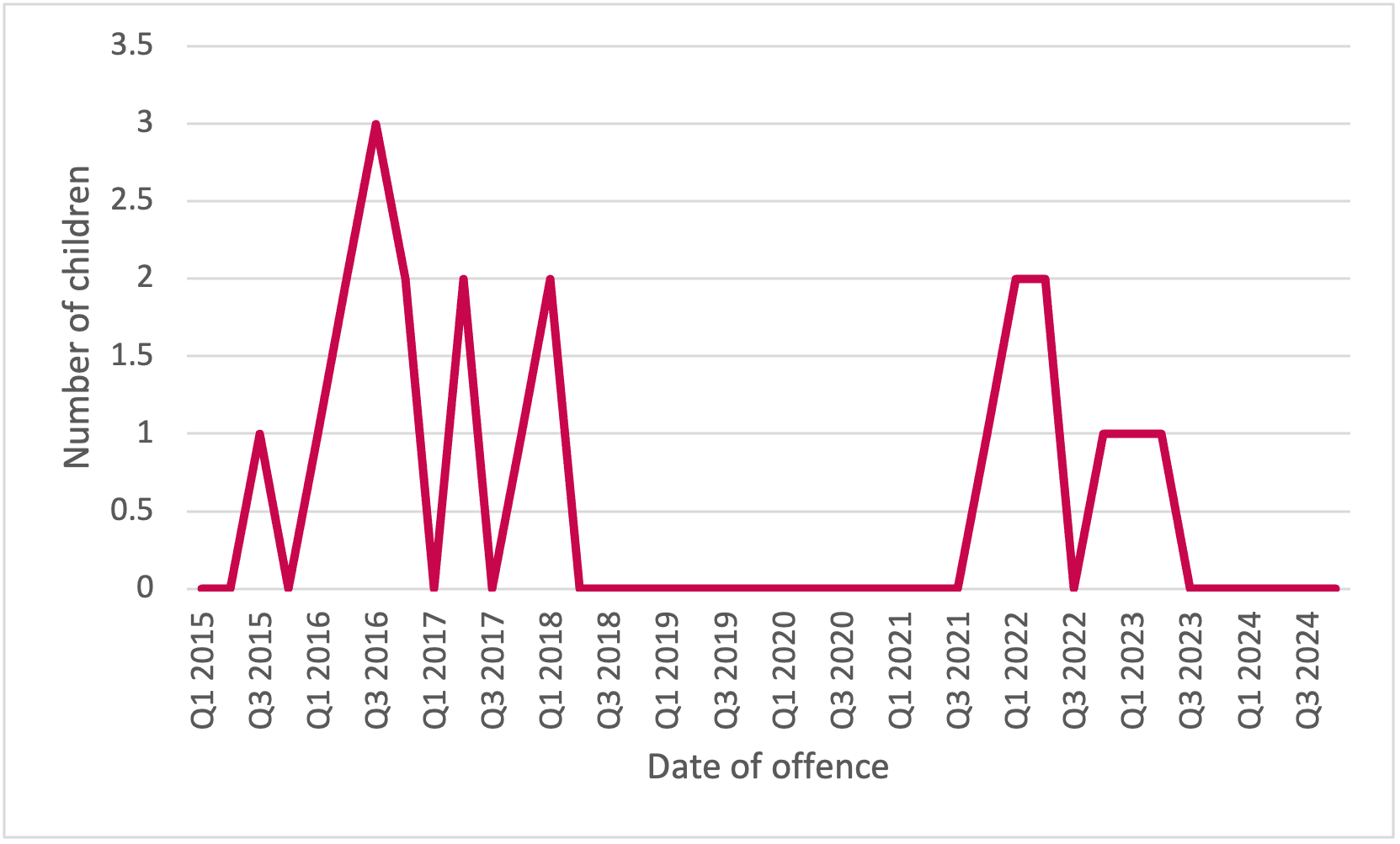

Figure 1: Terrorism offences committed by minors in England and Wales since 2016.

Minors involved in terrorist activity are most commonly linked to extreme-right and hybridised ideologies. However, this trend also certainly rings true for young people involved in Islamist extremist activity who have many of the same vulnerabilities and opportunities as their counterparts in other ideologies. Of the 55 children convicted of terrorism offences since 2016 in England and Wales, 40 percent were linked to Islamism. Figure 1 shows that this activity took place in two waves; the first correlated with IS territorial control while the latter emerged after the pandemic. While likely driven by the clarity which the Terrorism Act provides around Islamist ideologies, the 22 cases of young Islamist terrorist activity show an alarming trend. This crisis was compounded by the recorded 50 children who travelled to territory held by the IS group.

Young Islamist activity

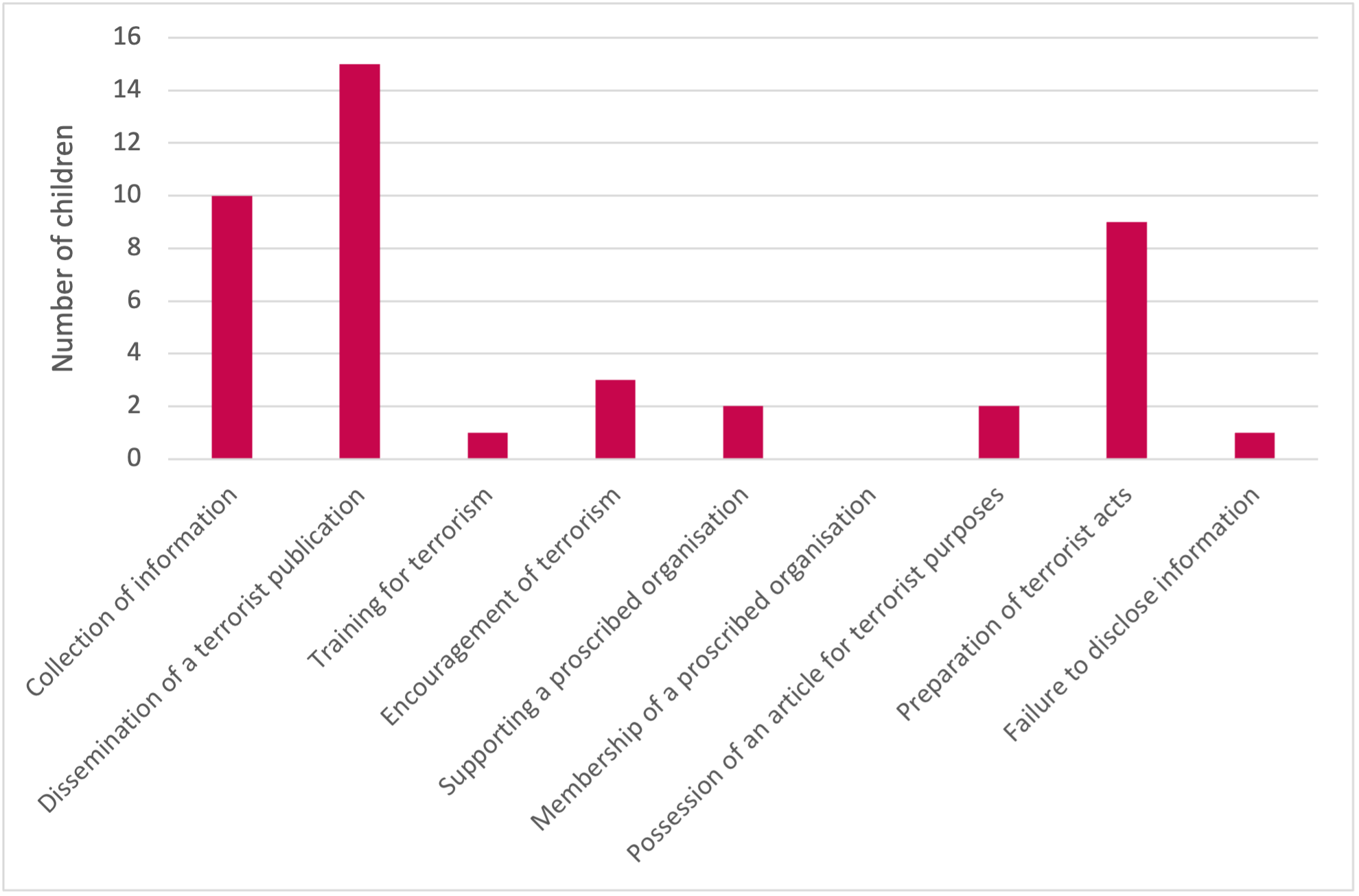

Data shows a broad range of offences committed by minors in England and Wales since 2016 related to Islamist ideologies (Figure 2). The most common activities were possessing or sharing terrorist publications or materials. These often included magazines belonging to AQ or the IS group which are shared across mainstream and fringe social media platforms as well as end-to-end encrypted chats.

Figure 2: Terrorism offences committed by minors in England and Wales since 2016 by type of offence.

Nine children had planned Islamist-related terrorist acts which includes both plans to travel to Islamist-held territory and attack plots. Many of these cases took place during IS group territorial control when unsuccessful travel plans by “frustrated travellers’” led instead to UK attack plots. This included a young woman whose online marriage to an IS group fighter at 16 motivated an unsuccessful attempt to travel to Syria, and later plans to attack the British Museum. This case exemplifies the significant vulnerabilities of young people, sometimes groomed or trafficked into extremism, as well as their capacity to plan extreme violence. Other recent notable attacks involving minors were planned for the Isle of Wight Festival and a Justin Bieber concert in Cardiff.

Young Islamist terrorist activity is incubated in online ecosystems which weaponise social isolation, poor mental health and neurodiversity, identity and community-searching, and thrill-seeking tendencies (Vale & Rose, upcoming). Meanwhile, offline environments also remain key vectors for radicalisation, including sometimes via family networks.

Protecting young people and society

Government and policies strategies have recently sought to determine better outcomes for children, introducing youth diversion orders for terrorism offending. This creates another backstop for children between Channel and criminal justice outcomes.

New social media regulation changes also seek to reduce the toxicity of online young ecosystems, reducing the risk of harmful content being served to youth by platform recommender algorithms. This could increase the friction between vulnerable children and online networks seeking to manipulate them.

However, the efficacy of these changes remains to be seen, and a lack of focus on fringe or gaming platforms where children can access extremist content may leave children equally as exposed. As the age of perpetrators decreases, and factors which influence their engagement shift, so too should our responses.

Conclusions

Twenty years on from 7/7, the chaotic and unstable global landscape has also contributed to the fragmentation of Islamism—both internationally and within the UK. While some forms of militant Islamism have metastasised into a virulent and persistent global threat, others, shaped by specific leaders and political realities, are now pragmatically but cautiously welcomed by governments across the globe, as is the case in Syria.

Hypercharged by social media and its access to new global audiences, Islamist networks are able to constantly adapt narratives and strategies, including coordinated efforts by ostensibly non-violent groups to normalise and mainstream Islamist talking points (often weaponising progressive language), laying the groundwork for extremist violence.

This has, in turn, meant that young people are increasingly able to access information and influencers capable of mobilising them to Islamist extremism, bringing with them a new set of drivers and vulnerabilities which must be addressed alongside harmful ideologies.

Despite 7/7 being their high-water mark in terms of casualties, the challenge faced by the UK from militant Islamism continues, but in an ever-evolving form. This threat is however increasingly shaped by the political realities, environmental factors such as local social dynamics, the West’s policies and responses to them, and the fluidity of the ideological persuasions of individuals within these groups and organisations. Understanding this should shape our ongoing responses to these ever-evolving challenges.

The second article in this series, ‘Twenty years on: Responses to Islamist terrorism in the UK since 7/7’, analyses how counter-terrorism approaches have sought to address the changing threat landscape, and can be found here.